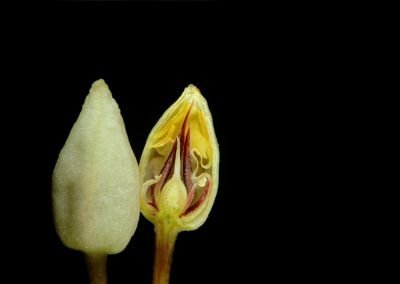

Growing & Harvesting

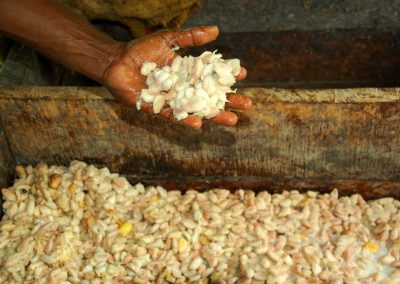

After the cocoa pods are grown and ripe, they are commonly harvested by cutting, or knocking, off a a tree often with a machete. The pods are then broken, and the beans are separated from the surrounding pulp. The beans are then set to ferment for about seven days, which results in the familiar chocolate taste. Harvesting pods when ripe is vital in the flavor profile; if the pods are not ripe, they will yield a lower percentage of cocoa butter or sugars in the white pulp, thus insufficient in the fermentation process, which in turn provides a weaker overall flavor. After this fermentation process, the beans are quickly dried to avoid any potential growths, and this is done by spreading them out, climate permitting, in the sun for five to seven days.

Once sufficiently dried, the beans are transferred to a manufacturing facility, where all excess debris is removed (twigs, small stones, etc.), roasted and then graded. The shell is then removed from each bean to extract the nib interior, which are ground to a liquid state resulting in pure chocolate in the fluid form, or chocolate liquor. This can then be processed to separate the two components: cocoa solids and cocoa butter (which can be read about <here>).

Blending

After cocoa liquor is separated, chocolate is blended with varying amounts of cocoa butter depending on the desired result. Many manufacturers will use an emulsifying agent, often soy lecithin, although few companies omit this agent in order to keep their product more ‘pure’ and GMO-free.

In the blending process, high-quality dark chocolate consists of at least 70% cocoa (both butter and solids), with milk at a minimum of 50%, and white containing about 35% cocoa butter (although no cocoa solids).

Mass-produced chocolate is argued to yield bad-quality chocolate, which is the spark for so many ‘small batch’ chocolate companies to arise, as they focus on quality over quantity. Believe it or not, some mass-produced chocolate can have as little as 7% cocoa; these companies (which we do not carry) incorporate vegetable oils and artificial vanilla as it is much cheaper and more efficient in masking poorly-fermented beans.

Back in 2007, Hershey and Nestle petitioned for the FDA to classify a product ‘chocolate’ with partially hydrogenated vegetable oils substituted for cocoa butter, in addition to artificial sweeteners and milk substitutes. Allow the FDA does not currently allow the legal definition of chocolate is the product contains any of these ingredients.

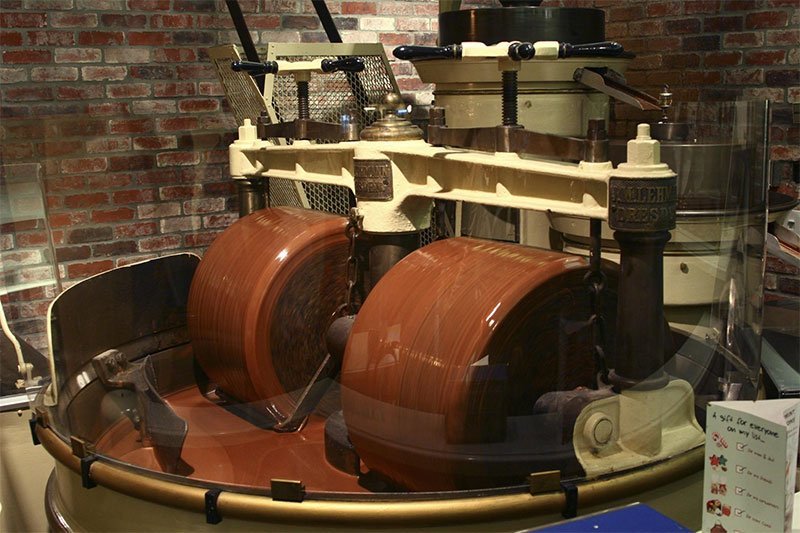

Conching

Once all of the cocoa has been blended to its manufacturers’ desires, the next step is conching. A conche is a large container filled with metal beads which act as grinders. Through the process, it keeps the chocolate in liquid state due to frictional heat. Prior to conching, chocolate has a grittier and uneven texture. The process breaks up these particles such that they are too small for the tongue to detect, hence the smooth texture. The length of the conching determines the smoothness and quality. Higher-quality chocolate is conched for about 72 hours, and lesser-grades for closer to 6 hours. Once conched, the chocolate mass is stored in tanks heated to 113 – 122°F until the final processing.

Tempering

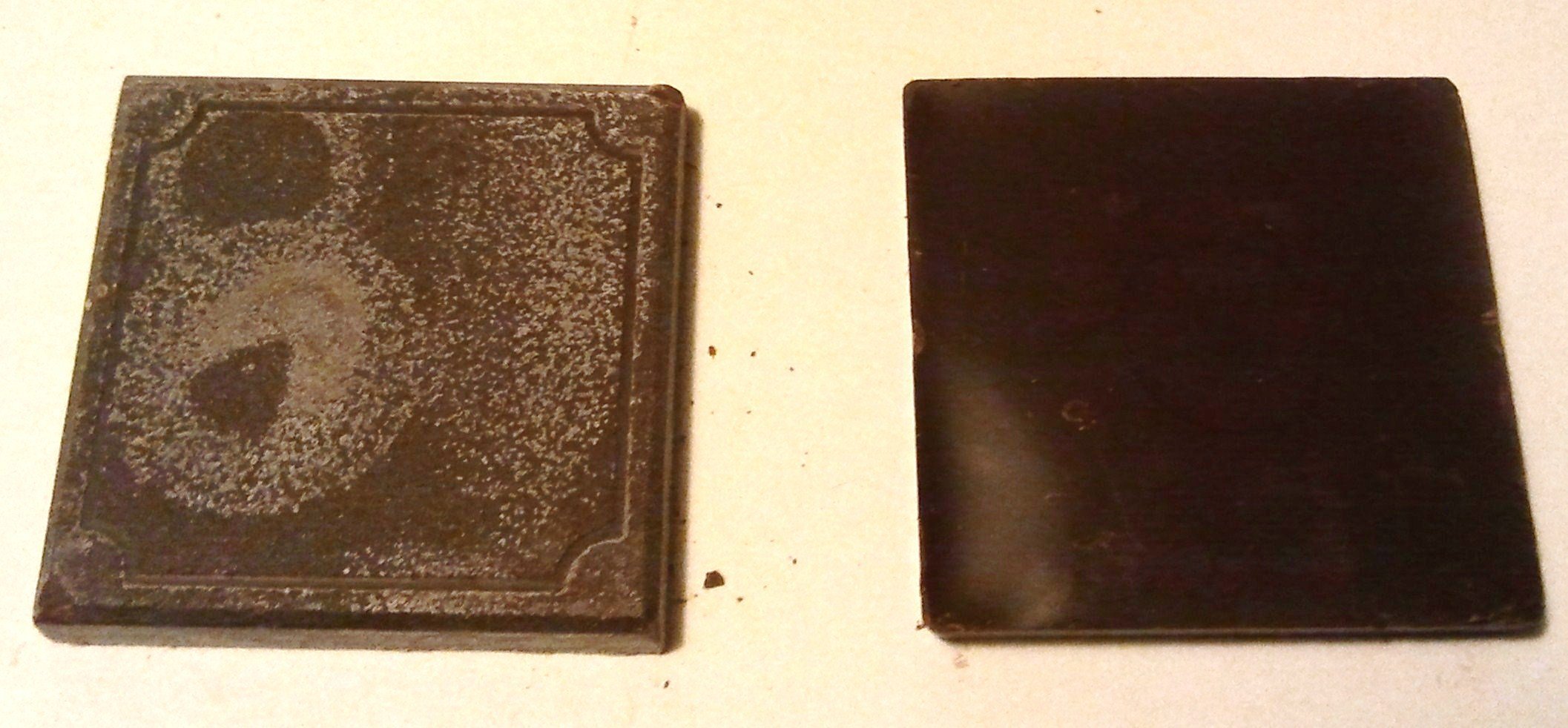

The final process is known as tempering. If chocolate is not tempered, then crystallization of cocoa butter often results, with some even visible to the naked eye. The gives a skewed visual appearance, and causes the chocolate to crumble as opposed to snap when broken. Uniform sheen and snap results from properly processed chocolate and are the result of consistently small cocoa crystals, which results from the tempering process. The temper is important to control, as even the slightest manipulation in temperature can skew your overall results. There are even chocolate temper meters, which works by measuring the temperature of a standard weight of chocolate as it crystallizes when cooled in a controlled way.*reword This is used to measure the various types of crystal forms IV, V (seen below) in semi-molten cocoa butter.

| Crystal | Melting temp. | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| I | 17 °C (63 °F) | Soft, crumbly, melts too easily |

| II | 21 °C (70 °F) | Soft, crumbly, melts too easily |

| III | 26 °C (79 °F) | Firm, poor snap, melts too easily |

| IV | 28 °C (82 °F) | Firm, good snap, melts too easily |

| V | 34 °C (93 °F) | Glossy, firm, best snap, melts near body temperature (37 °C) |

| VI | 36 °C (97 °F) | Hard, takes weeks to form |

The tempering begins by first heating it to around 113F to melt all six forms of crystals, which is then cooled to about 81F, which allows types IV and V to form. After some more agitation, the chocolate is heated to about 88F to remove any type of IV crystals, leaving just V. If this resulting chocolate is then excessively heated, it will destroy the temper, and this process will have to be repeated. The ‘best’ chocolate will have as many V type crystals as possible.

Storage

Storing chocolate is also an important step in retaining its flavor and texture. Depending on the variety of chocolate, storage temperatures can slightly vary, although ideally can be kept in 59-65F with a relative humidity of less than 50%. If refrigerated or frozen without a sealed containment, chocolate can actually absorb enough moisture to cause a white-toned discoloration, or chocolate ‘Bloom,’ which is a result of fat and/or sugar crystals rising to the surface of the product. If chocolate constantly fluctuates in temperature, and you do experience bloom, it will not affect the actual taste, it can be reversed by re-tempering the chocolate.

References

Sensational Chocolates. (2008). Sensational Chocolates: Discover the Intense Robust flavor of 100% ‘Grand Cru’ Chocolate.

International Cocoa Organization. (1998). What are the varieties of cocoa?

Schwan, R.; Wheals, A. (2004). The Microbiology of Cocoa Fermentation and its Role in Chocolate Quality.

Xocoatl. (2008). Harvesting the seeds.

College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources. (2010). Making Chocolate from Scratch.